AS I was growing up, on a Sunday morning in November, I would accompany my nan on the short walk to town where we lived.

We weren’t shopping, or just having a ramble to take in the country air. No, that little boy was attending the Remembrance Service with his nan.

While I may not have completely understood why we were there, I do remember my beloved nan was always quiet on these days – solemn as we stood in front of the stone war memorial adorned with bright red wreaths.

I can remember several times looking up at her to see a tear running down her cheek. But she never spoke. She just stood.

As I grew up, I came to learn more. Her big brother, Albert Hughes, had been a member of the RAF – a rear gunner on bomber planes.

“He had done his service,” she later told me, when I asked her about him. “He was coming home. But a crew needed a gunner and he went.”

He never did come home, but she struggled to say those words, or any others about him really. It was clearly still so painful.

As far as anyone is aware, my great-uncle and his comrades – in a Sterling bomber – were shot down somewhere between Britain and Holland.

Yet he was never forgotten.

Each year, my nan would point out his name to me on the large plaque outside the town’s memorial hall, clearly proud of her brother and what he did for the country, and I have done the same to my family.

And rightly so.

My great-uncle – Albert Hughes – is named on the memorial hall in Upton on Severn, Worcestershire. Picture: Google

More than a million British military personnel gave their lives during the First and Second World Wars. And thousands have in conflicts since, from the Falklands, to the Gulf and Afghanistan.

‘We will remember them’, the slogan goes. And we must.

My nan died almost two decades ago. Hardly a day goes by when I don’t think of her.

Yet on Remembrance Sunday, those thoughts are as strong as ever.

More than a century since the beginning of the First World War, we British continue to venerate The Fallen – as we should – honouring their sacrifice in the battle against fascism.

They fought for the right reasons. They gave their lives for good and the annals of our nation’s history will forever honour them and their deeds.

My memories of my nan, and my determination to continue the memory of her loss, of her big brother, have come back to me this week.

Not only because Remembrance is on the horizon, but because something else has loomed into view in the rear view mirror of our nation. Something we have passed and thought perhaps, left behind.

In 1807, the slave trade in the British Empire was abolished – but not entirely. Slaves in the colonies – excluding areas ruled by the East India Company – were not freed until 1838.

The British were involved in the transatlantic slave trade for more than 250 years. In the 1730s, it was the world’s largest slave trading nation, running highly-lucrative routes stretching from Europe to Africa, to the Americas and back again.

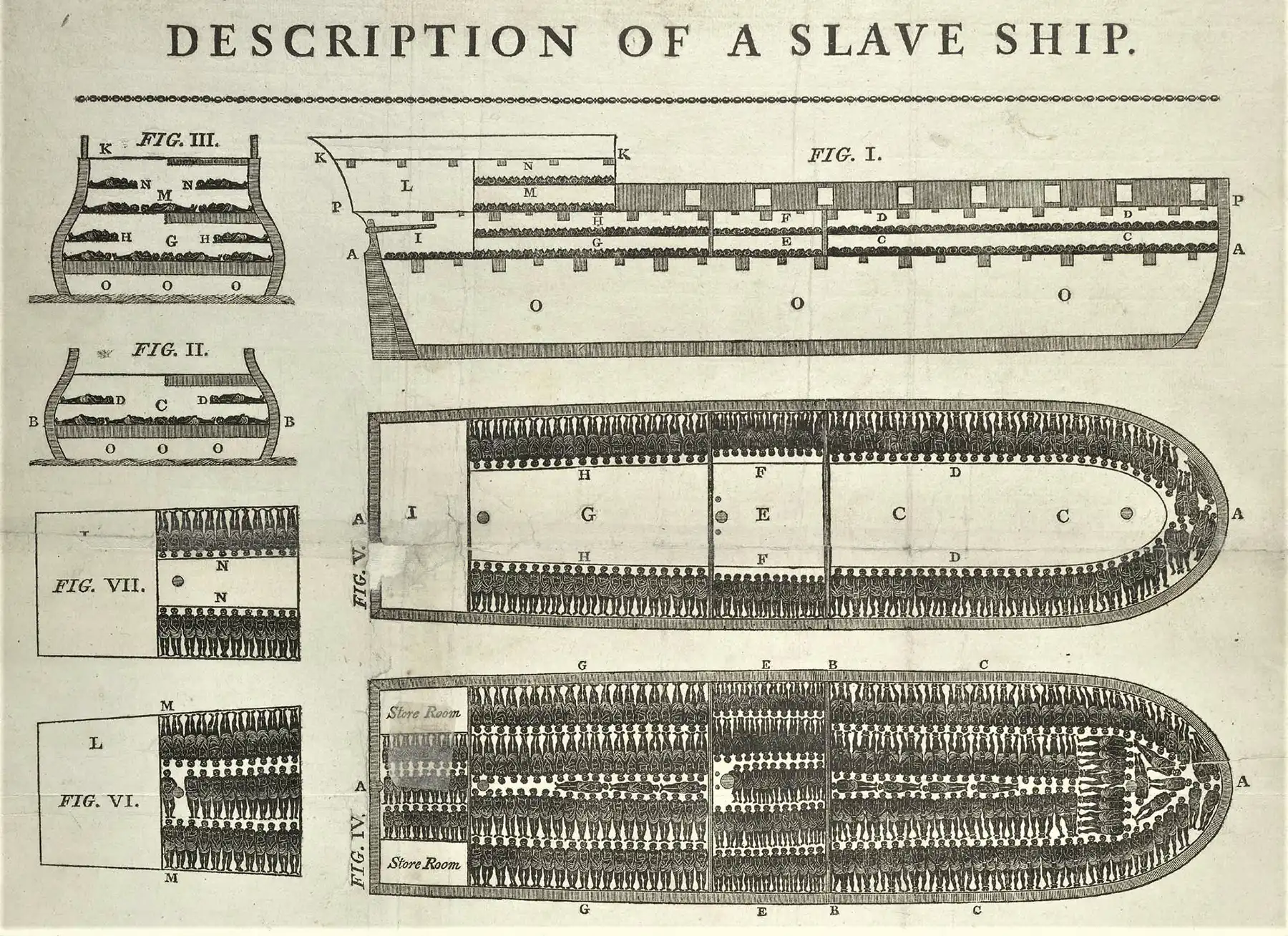

The vessels on ‘slave routes’, who took goods to Africa, before taking enslaved people from there to the Americas and back once more to British shores, were dominated by those bearing names of cities such as Bristol, Liverpool and London.

These ships transported more than 3 million African people, mainly to British colonies in the Caribbean and north America.

A diagram of the Brooks (or Brookes), a British slave ship launched in 1781. The ship carried enslaved African people on the brutal journey across the Atlantic. Picture: World History Encyclopedia

Off the back of the labour provided by those people, British society boomed – from the growing ports, to the industrial cities and countryside estates – thanks to wealth enslaved labour helped generate.

Our society – from the grand stately homes we wonder around on bank holidays, to the schools and universities where we learn – grew rich in untold ways.

All on the back of enslaved people.

Now, almost 220 years after the Act abolishing slavery was finally passed, the issue has once again hit the headlines.

Why? Because the nations we pilfered for produce and people think we owe them.

It’s hard to argue we don’t.

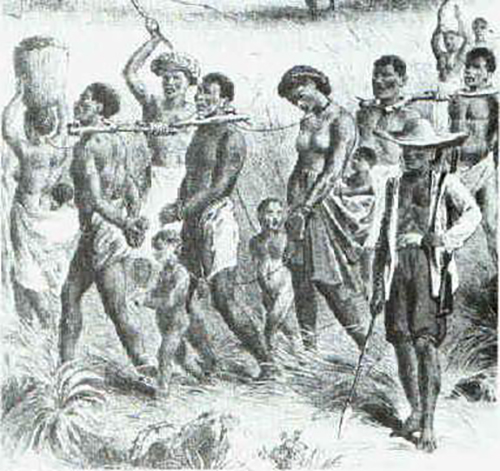

The British literally robbed colonial lands of not just produce, but people. Human beings. Taken from their homes and forced into labour.

We transported them – in largely inhumane conditions – to a far-away land, where they worked to make us rich, until they died.

The British developed an enormous enslaved population, backed by parliament and indeed, the royal family.

Plantation owners, their financial backers and traders themselves grew exceptionally wealthy as a result of dealing not in just produce – but in people. People deemed by parliament to be the ‘property’ of their owners, something to be used until the end of its useful life, then discarded, and a replacement purchased.

It’s a shocking reality none of us has ever really had to face.

And now, the nations so cruelly robbed think we should do something to compensate for that suffering.

I mention this in the context of my nan and Remembrance Sunday because, as I said, it is massively important we remember the history of our nation.

But that means remembering both the good and the bad.

As we rightly venerate The Fallen, so we should also honour those who fell due to the horrific actions of our nation, or our forefathers.

I am keen to honour the memory of my great uncle, and the memory of others who did the same. To remember the selfless sacrifice of my countrymen who gave their lives for their nation.

Therefore, I must also remember the dishonourable actions those same countrymen, those same forefathers, who used the lives of others to enrich themselves – and our nation.

There should be no selective memory when it comes to our country.

There is no shame in acknowledging the shameful.

Naysayers on reparations are right – they are not responsible for the slave trade.

I read an internet post – about slavery – that ended with the line: “Stop trying to make people feel guilty for things they didn’t do.”

Okay, but if we are to do that – ignore a historical act because it was carried out by our forefathers long ago – then we should, by the very same token, stop honouring the efforts of The Fallen, shouldn’t we? That too was long ago, and is a thing ‘they (we) didn’t do’.

No, we are not responsible for slavery. But nor are we responsible for the wartime heroics of The Fallen – yet we honour those efforts, claiming our collective pride in their actions, because it is the right thing to do.

Well, we should also claim our collective shame, because recognising our wrongs is also the right thing to do.

We are equally as responsible for the actions of the slave owners and traders as we are of our valiant war heroes, but choose to wash our hands of one of them.

But they are *our* slave owners, as much as they are *our* boys who gave their lives to defeat fascism.

I take enormous pride in honouring the sacrifice of my nan’s brother, my great-uncle, because I should. But I must also take enormous shame in the actions of those who enslaved others, also, because I should.

National memory should not be selective.

And recognising the prior faults of the British establishment does not mean I ‘hate my country’, or any such nonsense.

When your child makes a mistake, and you correct them, explaining why it was wrong – does that mean you hate them? No. Quite the opposite. You do it because you love them and want them to learn how to be better.

You want them to ‘know better, do better’, which is fast becoming a catchphrase in these pages.

So I believe we must remember all facets of our nation’s complicated past, and own them. All of them. From the valiant young who gave their lives fighting the Nazis, that we might live ours in freedom, to those whose lives we took while denying them the very same freedoms.

What reparations would look like, or would be, is a completely separate debate – and not for me to decide. But it seems to me there must be some way of us working with many Commonwealth nations – who remain ‘ruled’ by us, all these centuries later – to our mutual benefit.

Perhaps foreign aid could be targeted in a specific way, I don’t know. But that doesn’t mean I don’t see the need for it, or appreciate why nations may want to talk about it.

The nations, the people, we so abused need support to grow, to flourish as we have in so many ways. We forced them to help us – they should not be forced to make us recognise it. And perhaps we can help them, as well as ourselves?

Picture: America’s Black Holocaust Museum

We should at least have the decency to discuss the topic, rather than once again attempt to impose our will and try to bully them into submission, into silence.

To ignore the atrocities of our past should be as disrespectful as it would be to forget The Fallen.

For they both had nothing to do with me – with us – but we are all product of the outcome.

To deny it is to stick one’s head in the sand, to deny the suffering of others in a bid to deny ourselves the shame of actions in our country’s name.

The cultures and peoples we impoverished in order to boost our own wealth are entitled to something back, to some compensation, in one form or another.

For lest we forget, the only people compensated when slavery was finally abolished, were the slave owners.

The enslaved got nothing.

Parliament would not act to abolish slavery until they were sure those who benefited from it were compensated. Yes, you read that correctly.

While Jacob Rees-Mogg and his ilk may try to convince you Britain acted with great honour in leading the fight against slavery (spoiler alert: it didn’t), the fact is the abolition of slavery would never have occurred without slave owners being well compensated for the loss of their ‘belongings’ – *their* human beings.

The Bank of England says on the subject: “As part of the compromise that helped to secure abolition, the British government agreed a generous compensation package of £20 million to slave-owners for the loss of their ‘property’.

“The Bank of England administered the payment of slavery compensation on behalf of the British government.”

There are three memorials to those who suffered during the African slave trade. Yet there are countless statues of those who profited from it.

This is shameful. But there is no shame in acknowledging that.

Why are we so scared of doing so?

As the naysayers are so keen to point out – ‘it was nothing to do with them’, so why fear recognising the abuses – of remembering those who died and discussing the fact that maybe, just maybe, we owe them something?

We should all remember those who gave their lives. And we should remember those whose lives were taken.

PAUL JONES

Editor in Chief

Do you agree? You can drop me a line by email to paul@blackmorevale.net – but please, be polite!

You can read more of my opinion pieces here:

OPINION: My idea to solve the prison and employment crises

OPINION: ‘Please, boomer, stop telling us how hard you had it…’

OPINION: Why Liz Truss would be the perfect next Tory leader

OPINION: ‘Prime Minister, I’m not angry, I’m just disappointed’

Leave a Reply