“LOVE football? Win £50 million! Predict the European Championships 2016 Results and Win!”

Sounds good, right? And all you had to do was click a button (bearing the words ‘I want to win!’), and enter some personal details…

No one picked up the £50m prize, as far as we can establish. Of course they didn’t – the odds of correctly predicting every result in the Euros were astronomical.

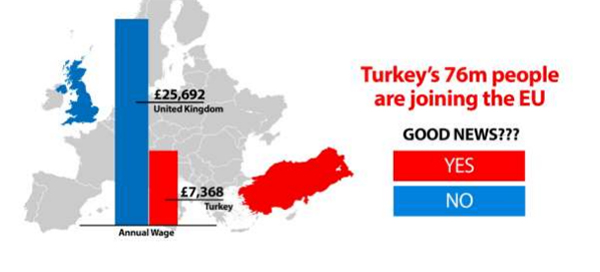

“Turkey’s 76m people are joining the EU. Good news???”

All you had to do was click buttons marked ‘Yes’, or ‘No’, and again, enter some personal details.

Despite the warning, and the certainty, in July 2023, the European Union decided not to restart membership negotiations with Turkey, effectively ending decades of discussions over the country joining.

The country – and its 76m population – has still not joined, almost a decade after that ad ran on social media.

What do those ads have in common, I hear you ask?

Well, they were both run by the Vote Leave/50 Million campaigns on social media in the run-up to the EU Referendum in 2016.

The result of that referendum, of course, has gone down in history. But the fact such ads were used to bring it about is not, perhaps, quite so well known.

The above examples are among thousands of ads that flooded social media during the referendum campaign – particularly in the week before the UK headed to the polls.

Details emerged as part of a probe into ‘Disinformation and fake news’ by the House of Commons’ Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee (DCMS), which published its final report in February 2019.

The committee concluded electoral law was “not fit for purpose” and needed change in a world of “online, microtargeted political campaigning”.

Ads like those above are part of such ‘microtargeting’. And it works. But how?

Often, when we use social media, we interact with content – a video, a photograph, a joke or news story – and that interaction is recorded.

Social media companies know what makes each and every one of us laugh or cry, what makes us happy, or perhaps most importantly, angry. And it remembers.

This data can then be used by advertisers – including political parties.

For example, someone passionate about the NHS will likely react to posts on that subject. They may have ‘liked’ pictures calling for support for nurses and doctors, or for the building of new hospitals. They may have reacted angrily to posts detailing our struggling health service.

Knowing that, advertisers can then target that person with ads claiming the EU takes away funding from the NHS.

The advertiser knows this person is likely to react to that ad, to have strong feelings on the subject. Who knows, it could even influence how they vote…

“Let’s give our NHS the £350 million the EU takes every week,” the Vote Leave ad screamed.

Again, all you had to do was click a button, labelled ‘take action’, and enter a few personal details. Not only have you seen something you agree with – from a political campaign – but they may well now have your details and can then pepper you with more, reinforcing your desire to vote for them.

You see how it could work?

But if this still feels a bit far-fetched – a conspiracy theory, even – it’s not.

In 2017, infamous political strategist Dominic Cummings, Boris Johnson’s former right-hand man who led the victorious 2019 election campaign, told a conference how he employed a team of data scientists to strategise the social media campaign for Vote Leave.

Dominic Cummings

“They ran messages experimentally on Facebook to figure out what things work and don’t work,” he said. “We basically dumped our entire budget in the last 10 days, and really in the last three or four days.

“We aimed it at roughly 7 million people, who saw something like one and a half billion digital ads over a relatively short period of time.”

The ‘Turkey is joining’ ad was one of them. So was the ‘£350 million for the NHS’ ad. And there were many, many more.

You can see more of them in documents released by the committee by clicking here (opens in a new window).

Without getting into other controversies surrounding how these ads were paid for, it is clear microtargeting social media ads works.

It gives campaigns the ability to tailor not only the adverts themselves – but who sees each variant.

Theoretically, using AI, millions of bespoke ads could be created in an instant – each one targeting an individual, complete with wording and pictures the party can be confident will stir the right emotions – ads that campaigns can be almost certain the reader will react to.

It’s as close as a campaign can come to guaranteed agreement, emotional reaction – what’s known in marketing as, ‘engagement’.

But the magic ingredient that makes these ads so effective, is data.

In order to make you react, the campaign needs to know what has worked before. As mentioned above, the data we give social media companies by reacting to pictures, jokes, comments, videos, is worth a lot to advertisers – including political campaigns.

“There needs to be: absolute transparency of online political campaigning, including clear, persistent banners on all paid-for political adverts and videos, indicating the source and the advertiser; a category introduced for digital spending on campaigns; and explicit rules surrounding designated campaigners’ role and responsibilities.”

That was part of the conclusion from the DCMS committee to this information, as it called on the Government to introduce new rules governing online advertising, including social media posts.

In response, November 2023 saw a ‘digital imprint regime’ introduced to govern online ads. This means political parties and campaigns must mark their ad with details of who it has come from – known as an imprint.

You will recognise them from political leaflets that drop through your door – they have a name and some details on the bottom to let you know who published it and which organisation they represent. This is what an imprint is.

And now they are required for digital advertising too.

It’s too late for the Brexit Referendum, but the Electoral Commission hopes it will help in the upcoming general election.

However, whatever the new rules, we can already say political parties are gearing up to use similar tactics.

Internet monitoring organisation Who Targets Me looks at political parties’ spending on digital advertising, including social media.

It analyses who has spent what, on what, and how that might tie into a political strategy.

For example, using the rationale above, the key to being able to target people is getting their data.

To do this, you need their permission. This is often given without thinking, particularly on social media, by agreeing to terms when ‘liking’ a page, or joining a Facebook group, or registering with the site itself.

So, political parties, politicians and advertisers want you to engage with them – like their page, join their group – partly to get that information.

Why else would Prime Minister Rishi Sunak spend more than £42,000 on Facebook ads – mostly on asking people to follow his page?

Well, one answer could be that if you’re gearing up for a general election, there is no time to waste in garnering people’s data.

And it worked – in December, his page follower count increased by around 100,000 people. That’s a lot of data to use when planning to create bucketloads of Facebook ads.

The PM has led the way on such spending. His total spend on Facebook, for example, conservatively estimated at around £150,000 so far, can be compared to that of one of his predecessors, Boris Johnson, who spent a total of £254,000 on Facebook ads during his entire leadership.

The famously-techie Sunak is set to eclipse that in weeks.

In November last year, he spent around £40,000 A WEEK on Facebook ads. That spending hasn’t continued into the new year, but with that kind of money being needed, is it any wonder the Government recently – somewhat under the radar – upped the amount of campaign spending allowed for general elections?

Targeted advertising does not come cheap.

And Rishi Sunak, while leading the way, is by no means alone in this tactic.

The Labour Party seems to have woken up to it in recent months, increasing its own Facebook ad spend.

In one week at the end of February, for example, Sir Kier Starmer spent £23,000 on ads. Rishi Sunak spent £16,000.

The UK parliamentary parties themselves, in the past month or so, spent around this much: Conservatives – £354,000; Labour – £230,000; Reform – £11,000; Lib Dems – £9,000; Green Party – £8,000, according to Who Targets Me?.

So all parties are spending, but the gap between the ‘big two’ and ‘also rans’ is huge.

As an example, after Chancellor Jeremy Hunt delivered the Budget on March 6, both the Conservatives and Labour launched Facebook ads.

The Conservatives spent a whopping £40,000-plus on a set of ads pointing readers to a ‘tax cut calculator’ which would helpfully tell you how much you will save thanks to their efforts, in exchange for your data – including your salary – of course.

Rishi Sunak posted this ad after the Budget on March 6

Labour, meanwhile, launched an ad calling for an immediate general election, spending around £4,000.

What about on a local level?

Pressure has been growing on the likes of Facebook as the impact of targeted social media advertising has become clear.

One thing introduced by parent company Meta in response is the Ad Library, a searchable database of all ads posted on Facebook – and who posted them.

We used this tool to search MPs and candidates in Somerset, to find out if they are investing. We searched between January 1 and March 12, 2024, to give us a more up-to-date indication of activity.

To give an estimate on what each candidate has spent so far this year, we took the centre point of Facebook’s details. The social media giant’s archive details spends with a range – between £100 and £199, for example – so we have gone in the middle, in that case using £150.

Here are the Somerset constituencies and what we have found so far…

Glastonbury and Somerton

Faye Purbrick

The Conservative Party candidate for the new Glastonbury and Somerton constituency has absolutely been ploughing the Facebook furrow.

The Ad Library returns around 50 ads posted by Somerset Councillor Faye in recent years.

Since January 1, 2024, she has posted 14 ads on Facebook, including posts on educaton, housing and transport.

Her ad spend with Facebook includes three ads on which she has spent more than £1,000, and two costing at least £900.

If we take a conservative view of all the ad spend, going down the middle – Facebook gives a range – it would mean the Conservative Party, listed as paying for Ms Purbrick’s ads – has spent more than £8,500 on Facebook in 2024 alone.

Some of the ads posted by Faye Purbrick, according to the Facebook Ad Library

Sarah Dyke

Ms Purbrick will once again be on the ballot paper alongside Lib Dem Ms Dyke, who became the MP for Somerton & Frome at a by-election last year, defeating the Conservative with an enormous vote swing.

She is favourite to take the Glastonbury & Somerton constituency, but has spent nothing on Facebook ads so far in 2024, according to the Ad Library.

Taunton and Wellington

Rebecca Pow

Over in Taunton Deane, Conservative MP Rebecca Pow – who will run for the newly-created Taunton and Wellington constituency at the next election – has also upped her game.

So far in 2024, she has run around 25 ads, according to Meta’s Ad Library, spending – using our average again – around £9,600.

Gideon Amos

The Lib Dem candidate going up against Ms Pow in Taunton and Wellington, Gideon Amos, has invested little and often in Facebook ads, spending under £100 each time, but doing it 25 times.

By our reckoning, he has spent around £1,250 on Facebook advertising so far in 2024.

A selection of ads posted by Lib Dem candidate Gideon Amos

Wells and Mendip Hills

James Heappey

The current Conservative MP for the Wells constituency – which will become Wells and the Mendip Hills at the next general election – has spent nothing so far in 2024 on Facebook ads.

Tessa Munt

Mr Heappey’s Lib Dem opponent in the new seat, former MP Tessa Munt, has spent nothing so far on Facebook ads, making this is low-spending constituency in 2024.

Tiverton and Minehead

Ian Liddell-Grainger

A long-serving Tory MP for Bridgwater and West Somerset, Mr Liddell-Grainger will this time stand in the new Tiverton and Minehead constituency.

So far in 2024, Mr Liddell-Grainger – who was first elected in 2001 – has spent around £250 on Facebook advertising, through a series of five ads, all costing under £100.

Bridgwater

Leigh Redman, a long-serving councillor for Bridgwater, looks set to stand in this new seat for Labour.

So far though, he has not invested in Facebook ads, spending nothing in 2024.

Ashley Fox, who has been selected as the Conservative candidate for Bridgwater, is also yet to invest in Facebook ads, according to the Meta Ad Library.

Yeovil

Marcus Fysh

Conservative Marcus Fysh might be feeling the pressure in the new-look Yeovil constituency. Formerly the seat of Lib Dem big hitters such as Paddy Ashdown and David Laws, it will be a target for the party at the coming poll.

However, Mr Fysh is yet to spend any money on Facebook ads in 2024.

Adam Dance

Mr Fysh’s rival in Yeovil, however, Lib Dem Adam Dance, has been active on Facebook.

In 2024 so far, he has paid for around 35 Facebook adverts. However, similar to his fellow Lib Dem in Taunton and Wellington, Mr Dance has opted to spend relatively little and often, with all ads bar one costing under £100 (the other £100 – £199).

We therefore estimate he’s spent around £1,900 with the social media giant.

In summary, the estimated spending of Somerset MPs – and candidates – in 2024 so far looks like this:

Faye Purbrick (Con, Glastonbury & Somerton): £8,500

Rebecca Pow (Con, Taunton & Wellington): £9,600

Gideon Amos (Lib Dem, Taunton & Wellington): £1,250

Ian Liddell-Grainger (Con, Tiverton & Minehead): £250

Adam Dance (Lib Dem, Yeovil): £1,900

One thing we can be sure of, is that these numbers will increase in the coming months as an election moves closer. So be aware of what you’re seeing alongside pictures of friends and family – and more importantly, why you’re seeing it…

- Look out for more details on this in the April edition of your Somerset Leveller – when we will start looking at who is seeing these ads…

Leave a Reply